Enable the perfect virtual assistant by capturing your life in real-time

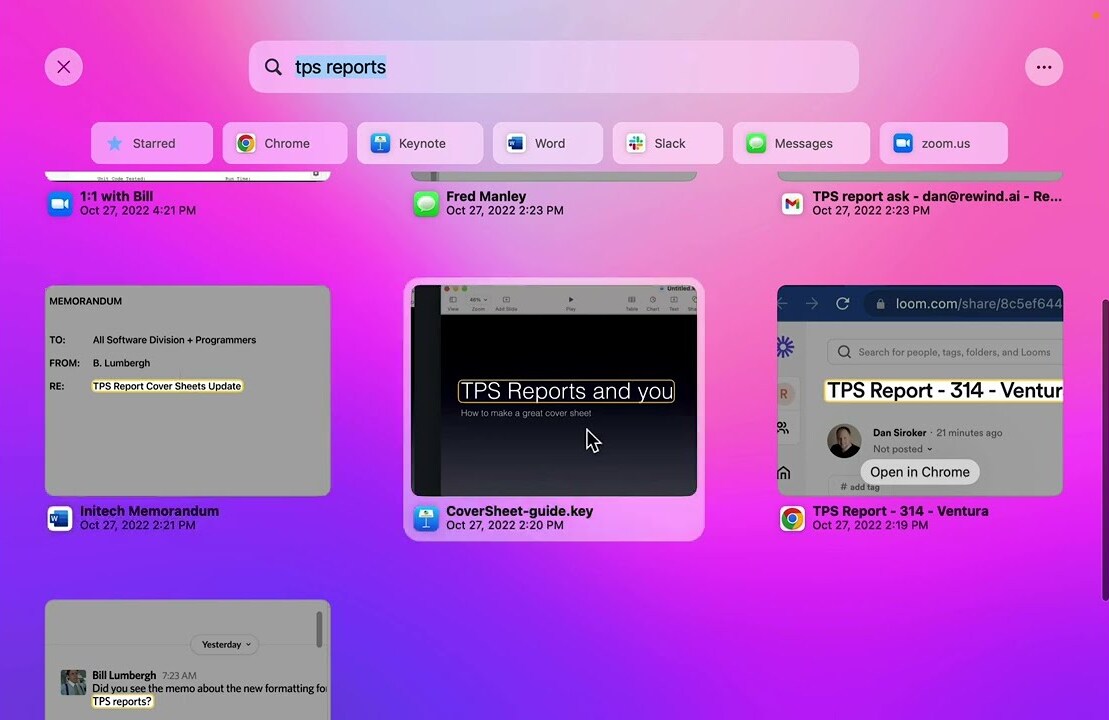

04 Jan 2023As an iPhone user who talks often about wanting to switch to Android, Apple’s new Journal app has both amazed and terrified me. What a seamless integration of my GPS location, photos, and messages that makes it feels like my phone understands me. It made me remember forgotten but cherished memories from even years ago. But one problem: I don’t remember ever opting into this! It was once heresy to deeply analyze our data in the background without asking permission, now it’s just status quo. Does anyone else remember Facebook and Cambridge Analytica? How they might have caused the presidency of Donald Trump? Is it really just the EU? Anyway, to me it really feels like devices are converging to this perfect virtual assistant that knows every little detail about us, but helps us significantly as a consequence. Years ago it was crappy Siri, but today it’s a little shirt pin that projects a hologram on your palm and speaks through ChatGPT. But as forward thinking as Apple’s Journal and this button are, and for how much they gloat about that fact, Iron Man actually thought of it first long ago with his AI butler, J.A.R.V.I.S (or I guess Marvel did)…

In his 2008 debut, Iron Man’s AI butler sparked the imagination of geeks worldwide who were tired of managing their own calendars and operating their own battle suits and whatnot. He “started out as just a natural language UI. Now he runs more of the Iron Legion than anyone.” He conversed with Stark anywhere, remained accessible anytime, and followed his every command dutifully. But what was most notable about J.A.R.V.I.S was not just being a conversationalist, but rather his omnipotent integration into the Stark’s life. He was simultaneously a strong AI that adapted to unseen environments, and interacted with the material world through sensors and IOT devices. Jarvis is essentially Iron Man’s second brain, one that responds to situations like a human, and has access to his eyes, ears, and other physical senses. The road to creating J.A.R.V.I.S ourselves is fraught with scary technical, ethical, and legal problems; such is the nature of an invasive super-assistant that knows everything you know. But with careful thought in designing and capturing our data, we can make it for ourselves, and most importantly for privacy, we can make it free like free speech, not free beer1.

What makes a great assistant?

To inspire the perfect AI assistant, let’s investigate what great human assistants do in the real world and translate them to their digital counterparts:

- Proactivity: They anticipate needs and take initiative. They understand their employer’s preferences, routines, and priorities, enabling them to address issues before they arise. In contrast, mediocre assistants tend to be more reactive, waiting for instructions rather than foreseeing and addressing needs in advance. This is the state of the current digital assistant landscape (Siri, Alexa, ChatGPT), no matter how good at conversation they are. Our digital assistant should be online and make decisions dynamically.

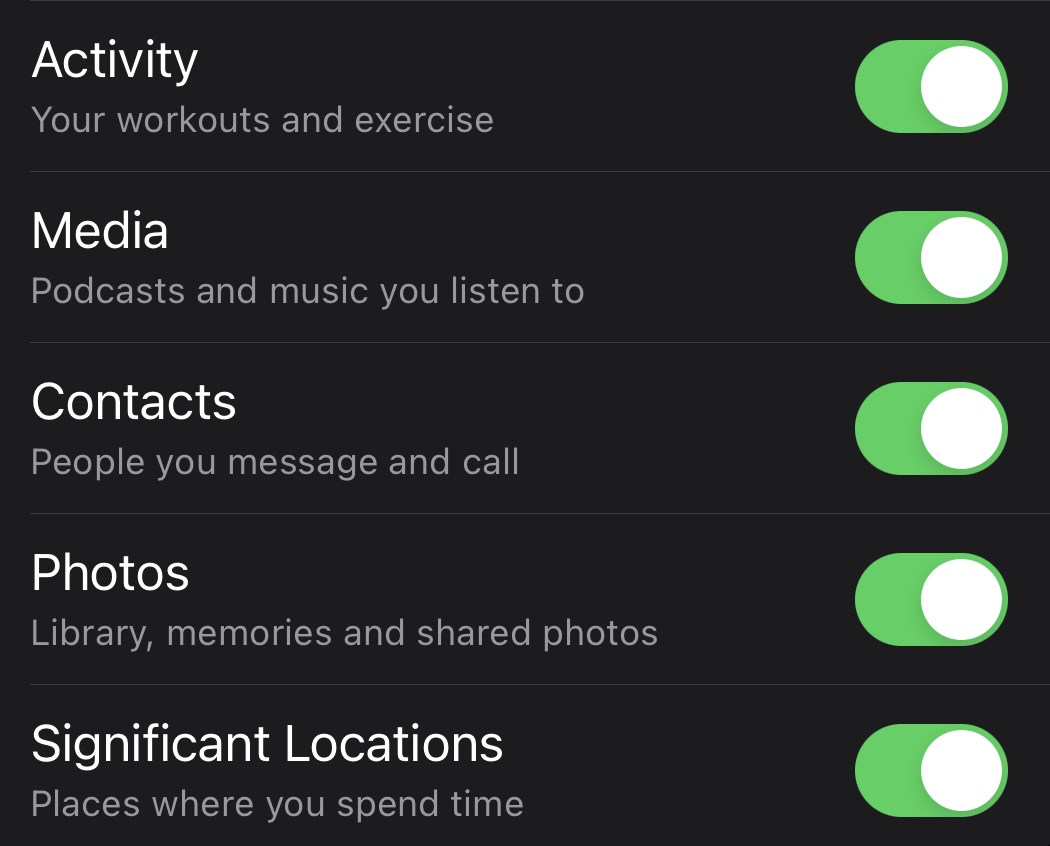

- Trustworthiness: They handle sensitive information with utmost discretion. Top assistants are trusted with confidential information and they maintain that trust unwaveringly. Mediocre assistants may not display the same level of discretion or judgment, like how sensitive data may end up in a Meta server where it’s used to keep people addicted to an app. Our digital assistant should ideally store all data locally inside an encrypted black box, and only serve the data to apps the user has explicitly approved.

- Emotional Intelligence: They are adept at reading emotional cues and responding appropriately, making them effective in managing relationships and conflicts. Mediocre assistants may lack this subtlety, leading to miscommunications or strained relationships, like an intrusive app that interrupts you at all the wrong times. As I’ve mentioned before, great software shouldn’t even make you aware that it’s present, and our assistant should be careful about the level of engagement it chooses to make.

- Tech Savviness: They are comfortable with a variety of technologies and software. This skill is about leveraging tools to improve efficiency and effectiveness. Less capable assistants might have limited technological proficiency, which can be a hindrance in a digitally driven environment. ChatGPT itself is not really tech savvy because it’s literally all talk and no action. However, with plugins it is able to invoke APIs to change state outside of its sandbox. Our digital assistant should do the same.

But now that we know what we want in an assistant, how do we build it? Let’s assume that we’re going to be using a large language model (LLM) to produce text as the primary means of communication with the user. After ChatGPT’s immense rise, developers worldwide enthusiastically tried to build assistants purely through an LLM. There’s about a million “GenAI assistant” startups that do exactly the same thing: GPT-4 API + custom prompt + their proprietary plugin and UI. While the architecture behind LLMs and embeddings are incredible, it’s no wonder these startups tend to look the same after a while… No, if we want Jarvis, we need to expand our framework of thinking from not just training bigger language models, but making them as relevant as possible through tailored information banks. Just like how Apple consolidated our photos and locations to produce journal suggestions, our assistant needs to “keep up” with our lives, and understand our current thoughts and actions. To do this, we need to take advantage of a recent key development in LLMs: separation of the knowledge base from the text producer. LLMs implicitly encode a knowledge base into the text producer due to the sheer quantity of information on which it was trained, but tailored and accurate systems can’t rely on this. They need to Retrieve relevant data from an external store to Augment the text Generation. The way to create a second brain is first to share our physical senses with language models. But people seem to have not picked up on the key fact that J.A.R.V.I.S would need to consume contextualized real world data, not a purely digital knowledge base. This hypothethical physical-senses RAG sounds pretty far fetched, and there’s no guarantee it’s feasible. This would technically make our assistant closer to an autonomous car than a chatbot in the way it interacts with the physical world. The next part of the formula after data retrieval is to apply it to produce some useful and relevant output, which we’ll get into later. But now for our main question: what data do we even need to collect to empower our assistant to be maximally relevant?

Introducing continuity

I opened by mentioning Apple’s journal suggestions feature; well they also provide an API for any app to latch onto the data. Continuity is my Linux counterpart to this API. I know the virtual assistant functionality I described above is incredibly complex and subjective, so I’m not attempting it. Instead, I’m only enabling it through a data collection backend that captures and preprocesses a diverse set of real time data, or the RA in RAG. I mentioned that the perfect assistant would ideally have access to our eyes, ears, and some other combination of senses. Let me be more specific about that data, collected from either your laptop or mobile phone:

What data will we capture?

- Devices’ screen contents: Everything you see in the digital world, which comprises text, pictures, and videos

- Voices picked up on microphone: Everything you hear, including your conversations

- Messages and emails: The digital communication with other people

- Browser history: The digital information you’ve seeked and consumed

Furthermore, we will contextualize each of these 4 real time data types with 3 more attributes:

- GPS location: Where you did something

- Time of day: When you did something and for how long

- Device usage patterns: How you used your device in a “session”

Storing these real time streams could easily defeat modern hard disks, so we have to be careful about what data we include and leave out. Surprisingly, we can apply the operating systems principles of orthogonality and composability to reason through these decisions. They are properties on which to evaluate a set of primitive functions, which can be like the syscalls, instruction set, or standard library. But if we relax our definition to include information, not just procedures, I think you’ll realize that the same framework of thinking translates to data collection too.

Orthogonality is the property that the components of your primitives set each adds a unique dimension to the overall set, so the cardinality of the set can be minimized. This is how the principal components of a dataset can form a smaller basis that captures maximum variance. We need to ensure the types of data we’re collecting don’t overlap each other in terms of the information they provide, because otherwise, there would be redundancy that costs us unnecessary computation and disk usage. We’re storing the screen’s video stream alongside the extracted text because the images you see are often just as important as the text you read, while the latter can be viewed as just a cache for efficient searching. We could query tons of user data from online APIs, but instead let’s stick with messages/emails and browser history, because I believe these are the two most important forms of digital text: communication and knowledge. However, we can delete the audio feed after extracting text conversations, because the former is just an analog encoding of the latter. The three pieces of contextualization are as simple as possible, and as we’ll see can still provide a great deal of context about the data. Instead of storing who you hung out with, you can infer this based on messages + time of day. Or instead of storing the addresses, you can look them up using some GPS location where you were at for a while. To avoid repeating calculations, these abstract processed pieces of information can simply be cached and reused every time they’re queried by an app.

Composability is the property that our primitives can be combined in diverse ways to express any complex use case. Through some combination of the components of our dataset, can we answer any question about the user? For instance, can we infer the user’s intentions, their thought patterns, their plans, or their emotional state? We’ve already reduced the cardinality of our primitive set by ensuring the components are orthogonal, but now we need to ensure our primitives are in a potent form that requires minimal overhead to extract maximum knowledge in order to answer questions of arbitrary complexity. This means an app should be able to request visited addresses from our GPS locations, conversations from the audio, high priority messages, or filter miscellaneous search queries. These abstract pieces of information readily allow us to combine and answer questions. For example, if you texted your friends to meet up at 7, but then your location was there 2 hours late because you were binging Netflix, that gives the AI agent a lot of context by piecing together a story, something that’s only possible if it can compose multiple sources of information together. Like I mentioned above, this is exactly what Apple’s Journal and Photos apps have achieved to a high degree of polish, and it makes the user feel like their devices understands them.

How will we capture and process the data?

It would be real dandy if there were a simple way to easily capture all of this real time data, but what I’m describing is quite the complex intersection of data science and telemetry. Luckily, while investigating this idea, I came across a promising MacOS app called Rewind that solves half of the equation. It collects your real time screen video stream, stores it in highly compressed archives, extracts text through OCR, and enables semantic searching through text embeddings. The real world application seems darn compelling to me, and a whopping $350 million valuation seems to agree with me. I thought this would be a wonderful starting point for my envisioned data collection backend, but being a MacOS app, it’s more proprietary than my own two hands. Rewind being a traditionally monolithic app that tightly couples the UI with the data capture/embeddings backend makes the latter useless to me. Nevertheless, another data enthusiast online analyzed the app’s requested permissions, shared libraries, and filesystem footprint to reverse-engineer its functionality and implementation.

Luckily, there isn’t any unique functionality that we can’t replicate ourselves with an open source pipeline. But after exploring what such a pipeline necessitates, I realize how behind the Linux (and Windows) ecosystem is in abstracting advanced functions from app developers. It makes perfect sense why most system apps start in the Apple ecosystem: not only can they make good money off of it because of the conventions of the App Store, but Apple includes a vast and easy-to-use library of ML models on every device by default. On Linux, image classification, segmentation, and OCR would require bundling and integrating 3 different vision models, and every app would need to bundle their own. This leads to wasted memory, disk, and developer effort utilization because there can be multiple copies of the same model across programs due to static linkage. While on Macs, this is all accessed through the VisionKit API. Obviously Apple isn’t doing much special apart from good ecosystem and API design; after all, Intel and Nvidia chips both provide the same degree of hardware acceleration, even specifically for neural network algorithms (GNA). But ease-of-use clearly goes a long way in incentivizing fast-paced innovation, which is vital in an incredibly bullish market. I believe that moving forward, Linux userspace must have a similar unified API to foster the next generation of ML powered system apps. But I digress…

Here is a detailed overview of the components this data collection backend needs:

- Screen contents capture (scrot): Take a screenshot at a constant interval, say every other second. This is a very low overhead operation and should happen continuously.

- Video encoding (ffmpeg): Encode a sufficiently large folder of screenshots into a highly compressed H.265 video. This is a costly operation that should be deferred until the user is charging their laptop.

- OCR (tesseract): Extract the text from each screenshot and store it in the database with a timestamp. This too is a costly operation that should be deferred.

- Audio capture (ALSA): Record some short interval of audio using the arecord tool from ALSA. Sleep for long durations between every recording interval to minimize battery strain.

- Conversation recognition (whisper): Extract any voices from the short audio interval, and if any are found, record the duration of the conversation. This can be done efficiently with OpenAI’s whisper voice recognition model.

- Email scraper (IMAP): Scrape recent emails using imaplib in a Python script that is activated at regular but infrequent intervals through a cron job. Another low overhead operation.

- Browser history scraper (sqlite3): Scrape browser history from Chrome’s sqlite history database. Low overhead and activated at same time as emails.

As for the contextualizing data, obtaining the timestamp is trivial through the time command or any standard library.

- Device usage patterns (uptime): Usage patterns are tricky to define, and some ideas are identifying what applications you’ve used and for how long, what ratio of active user input to idle time, or whether the user is typing or using the mouse more. But for this prototype, let’s start by using system uptime as a proxy for how in the “zone” you are. This can be easily found by reading /proc/uptime.

- GPS location (MLS): Record the user’s current location at regular intervals. We can use the exact same method your phone uses to get your location, which is WiFi-based geolocation. Phone’s don’t actually have GPS hardware, so they approximate using what WiFi networks you’re near and with what strength. We can collect the network’s data using NetworkManager’s cli, and then use the free Mozilla Location Services API to get a GPS location.

How will we store and secure the data?

Great! That’s completely feasible to implement, and with some intelligent computation deference, it can be very battery efficient as well! Now for the next problem, how do we persist this data? Simple, we use a combination of compressed archives to store the raw video and audio feeds in batches, CSV to store all the emails and searches, and a sqlite database to store the contextualization (time and GPS location). The space complexity of this app is O(video + audio), but we can take advantage of the H.265 and Opus standards that achieve incredibly high compression ratios for free. This is a similar approach that Rewind uses, so we can “borrow” their schema to save ourselves a lot of headaches down the line.

The other side of the coin is security: this is very intrusive data that malicious programs could freely access. Security by obscurity has backfired many times, and it doesn’t even apply here because this is an open source program. It would be frightening if an attacker had free access to our conversations and GPS location at all times. That’s why we need to encrypt our data at rest, ideally using public key cryptography. I saw an idea I liked where the public key is used to append data to the store and generate embeddings, and the private key is used to search through them. This requires encrypting every entry (recording archive + database row) separately so we can decrypt as little as possible at a time. Our storage approach plays quite nicely with on-disk encryption: we can use a cryptographic standard library to encrypt outside of continuity before we write an archive/entry to disk but after we generate the embeddings, and decrypt through continuity when the user or trusted app searches. How is the data secure if we have searchable unencrypted embeddings? Because the embeddings themselves are stored in a latent space that doesn’t mean anything outside the context of the exact same embedding model used to generate them. But cryptographically speaking, you can gain similarity information by comparing the dot product of two embeddings, which means there are less bits of entropy than desired from encryption. Plus, if an attacker gains access to our embedding model, they can generate a large bank of (plaintext, embedding) pairs and deduce keywords and common conversations. But this seems like a pill we have to swallow until someone figures out how to make encryptable embeddings.

How will we query the data?

Now for the final piece of the pie, actually using the thing through an API. To recap, at this point we have a folder on our hard drive containing:

- Compressed archives of video and audio files

- CSV file containing emails and browser search history

- Sqlite database with encrypted entries of time, uptime, and GPS location

But an app developer creating J.A.R.V.I.S doesn’t want to sift through none of that. Instead, they should be able to make string searches, whether exact or semantic, on all the different types of data capture. Furthermore, they should be able to qualify these searches through the context, meaning they can search for something at a specific time or place. I’ll need to put more thought into the specifics of the API to keep it simple yet powerful, so you’ll be able to find it in the git repo in the future. The data is encrypted and compressed in small batches at rest, so the backend should decrypt and decompress as little as possible per query. Since we’ve already generated text embeddings that are unencrypted, searching is ~O(1) instead of O(n), which is important in a real-time application since n does indeed grow linearly with time. Another interesting topic is that embeddings work on more modalities than just text, including image and audio. My thought process was that searching with images or audio doesn’t seem intuitive to use in an interactive application because it lives in a text-driven environment, but it may be worth experimenting. It could be a form of implicit search that brings up past instances you were in a similar location, for example. Finally, there must be a way to authenticate the callee, which can be done by maintaining a read-only list of approved applications to interface with the data. Adding a new app will require prompting the user with escalated privilege.

Designing this program was quite the ride, so thank you for reading this explanation. Perhaps if we provide a unified API for next-gen applications, compress and encrypt our real-world data generously, and rely on the perfect transparency afforded by open source licensing, then our lives are about to get exponentially more automated.

-

This is a classic Richard Stallman quote that means like free speech, you can use it with little to no restriction, unlike free beer, which you can use at no monetary cost. ↩